Over the years I’ve seen lots of demergers by listed companies and most have been more or less successful at creating value. AGL’s effort so far is a case study in how to stuff it up.

- Seemingly no agreement between Board and management.

- Premature announcement with close to zero useful information for investors and their army of advisors.

- No commitment to separate listing, which is the most fundamental rationale for doing it.

- Captain and the ship part company mid journey.

At this rate AGL will almost single handedly give demergers a bad name. Having said that we’d be the first to accept Brett Redman’s comment: It’s hard. Still that’s all the more reason for working out the details first.

Summary

Demergers are done for the benefit of all stakeholders, but particularly equity owners and the company work force.

Basically, demergers allow shareholders to pick and choose which bits they want to own. This honors the most fundamental separation of duties of public companies embodied in the theory of finance.

Management specialize in managing without thinking of the implications for individual shareholders and shareholders own portfolios to minimize risk for a specified return.

Management benefit because they can get on with managing with clarity of purpose. The job becomes to maximise the value of the business they have. More broadly freed from “constraints” new ideas can be implemented.

New energy, so to speak, is released from its dormant state inside the dead hand of a confused monolith.

ITK has no knowledge of the interaction between AGL ex CEO, Brett Redman, and the Board. If we were asked to speculate, our view would be that Redman wanted the demerger but there was Board Resistance.

Equally, it could be the other way round. This led to the demerger being announced prematurely, but not with any commitment beyond functional separation.

As tensions grew, Redman bailed. Now the Board is publicly committed, but does it know what it’s doing?

Transfield, where Graeme Hunt was CEO, did close to a demerger, or at least separately listed its generation assets via Transfield Services, and that was successful when taken over by Ratch. So maybe there is some background.

Certainly, we see a bigger role for the advisors, Macquarie Bank, who also assisted AGL with the equity raisings to buy the coal generation assets in the first place. They should understand the PrimeCo story well.

Success has many parents and failure is an orphan. I could write a long article about the events leading up to the demerger but the long and the short of it is that all the significant coal generation decisions were made when Michael Fraser was CEO and Jerry Maycock Chair.

Those folk took investors for fools, imagining that carbon wasn’t a major issue and that investors would value near term profits more than long term value creation. Who cares, that was then and this is now.

Articles in the AFR have emphasized that “Prime Co”, the proposed vehicle to hold the coal and majority of gas generation assets, will not be able to support much debt and has “huge” closure liabilities.

In our view this is possibly misconceived. Most fundamentally demergers in the first instance neither create nor destroy value. The demerged business, at least initially, can support exactly the same amount of debt in aggregate.

If banks wont lend to Prime Co, neither should they lend to AGL.

And the clean up liability can be managed. The cost estimates are very far from locked in.

Specialists in clean up liability management may be able to do much more, most obviously by deferring parts of it while the sites are used for other purposes but in general by more explicit plans and cost management.

PrimeCo, where much of the initial value and yield will lie, despite weak prices and declining volumes, will have to wait for another opportunity.

New AGL

I’d like to spend a bit of time thinking about the issues of “New AGL”, let’s call it NAGL the retailing business. Unfortunately, due to the non information AGL has provided, all the estimates we show are probably going to be way off the mark.

The risk of embarrassment is high, but as a 3 time winner and perpetual trophy holder of the annual “foot in mouth” award at JPMorgan’s Australian predecessor, Ord Minnett, I am good friends with my embarrassed self.

To start with, based on historic segmentation, NAGL will not be all that profitable, at least not without assumed earnings from its firming portfolio of Southern Hydro and Barker’s Inlet gas.

The table below is taken directly from the 2020 Annual report, save that we have allocated 70% of reported centralised expenses (head office) to NAGL and 30% to Prime Co.

The table above ignores the hydro and the Barker’s Inlet gas generation assets that will be allocated to NAGL. These would, for sure, increase net Ebitda. The main hydro assets have about 700 MW of capacity generating a bit less than 1 TWh per year.

Barkers Inlet provides a further 200 MW. We assume that about 800 MW of caps can be sold at about $7/MWh which provides around $50 million of revenue/Ebitda. See table at end of note for estimate.

The table further shows that 5/8 of the total gross margin is in consumer electricity and about ¼ of gross margin comes from gas retailing.

Depending on your philosophy, and ITK thinks climate change is the foremost driver of most things that happen in the energy sector, you won’t hold out much hope that the gas gross margin can be sustained indefinitely.

Nor is there any meaningful chance of a sustained lift in consumer electricity volumes, or at least not without significant penetration into behind the meter dispatch control or further changes to Government policy to encourage EVs etc.

There is the perpetual hope of a significant margin shift in large electricity but historically that has proved a mirage.

Again the only way it could be different is with some dramatic change in approach.

AGL is a natural large business retailer due to its ability manage prudential margin requirements. At the moment the business electricity contributes to overall return on capital because the unit hedging costs of a large diversified portfolio are smaller.

Put another way the portfolio with the business volumes has a better load shape.

Still the IT costs and finance costs are non trivial.

In a world where bulk energy comes from wind and solar you want flexible loads and above all daytime loads.

So for instance large bricks and mortar retailer loads look good if you have a solar shape, as does daytime office worker loads, etc.

Why doesn’t NAGL look all that profitable? You might argue the problem is that AGL’s internal accounting shifts all the profit into Prime Co (the generation side of things)

NAGL’s natural electricity cost is about 1.66 times what coal generation gets

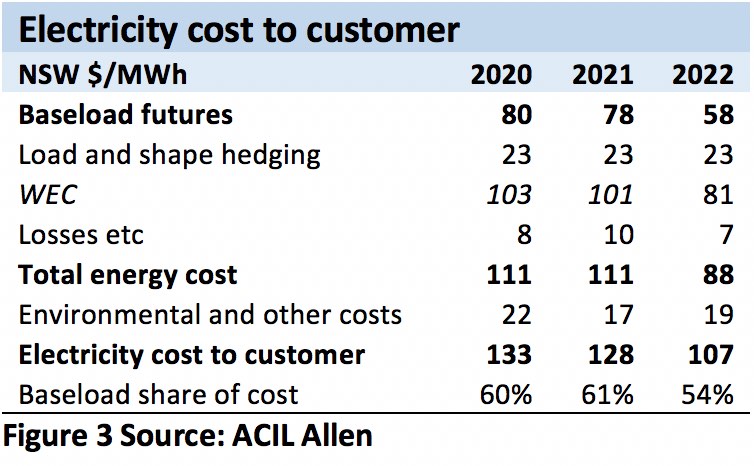

An electricity retailer has to get its bulk energy, then it has to hedge both the quantity and price, cover line losses, fees and then environmental costs. ACIL-Allen’s [ACIL] analysis for the Default Market Offer [DMO] is summarized below. A new report is due shortly.

It’s not the absolute estimate of the baseload cost but the relationship of that to the final power price that’s of interest.

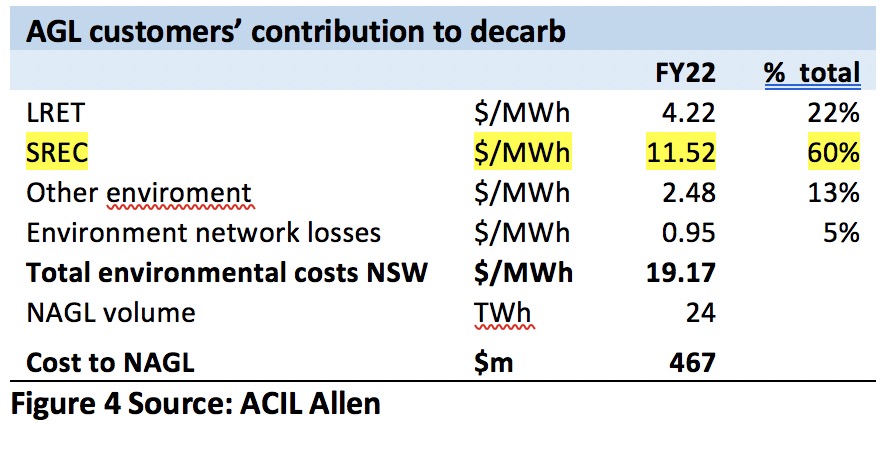

Using ACIL estimates for NSW FY22 AGL customers would pay about $450 m of environmental costs of which about $250 m is payments to rooftop solar customers.

The fundamental reason for the SRES being as high as it is, is because the lifetime environmental benefits of SRES are paid to the customer up front.

So even though rooptop solar generates about 6% of electricity in the NEM, the STC % is about 24%, that is about 43m STCs or 160 TWh of eligible consumption NEM wide. Underestimation of this market has cost traditional Gentailers dearly and AGL is amongst the most guilty.

In AGL’s own accounts green compliance costs are around $600 m per year, or $26 /MWh . That $600 m is an astonishing number, bigger than NAGL’s direct opex.

In our view it represents the best opportunity for NAGL to improve its profitability. But it will take a lot of commitment and time. Mainly commitment. Until management fully internalizes what ever goal it sets itself nothing will be achieved properly.

If AGL wants to be a multi product “services” business so be it. Personally I think that’s nuts, but maybe AGL can be a telcos provider, an internet provider, write home loans, sell insurance products, sell petrol as well as electricity and gas.

Who knows.

Personally I think it’s pretty hard just being a green electricity retailer and working out how to get positive net promoter scores and keep costs down.

Origin is doing well in embedded networks, an extension is community networks, orchestration of behind the meter, integration even partnering with a network such as Ausgrid. In short, recapturing the behind the meter space.

To me there are still possibilities, in the core business, but maybe that’s too hard. Maybe AGL should give it away like it’s given away its wholesale gas business and be a world beating services platform.

Low renewable credentials

AGL has about 5 TWh of wind and solar assets, almost none of which is directly owned, about half coming from the 20% investment in PowAR and about half from windfarms where output is purchased under what is essentially a leveraged lease.

This compares to around 24 TWh of sales volume. The figure below ignores Southern Hydro generation volumes, but those are typically pretty small as the hydro is for firming power not bulk energy. Same for Barker’s Inlet gas which is notionally, included in NAGL.

AGL doesn’t capture, so far as we know, many if any SRECS. It has recently bought two large commercial solar installers [Epho and Solgen] which may help going forward and have from memory as much as $100 m in revenue a year, plus whatever SRECs are associated.

It’s a start.

Here at ITK we have made a projection of AGL’s energy cost excluding environmental bits.

We used our own flat load price projections but caution that these are materially lower than consensus and influenced by our view of ongoing new supply both in front of and behind the meter and perhaps not enough coal generation closures explicitly factored in.

The rationale for how prices can be below the new entrant cost of solar or wind and around the marginal cost of existing coal is that State Govt policy will continue to force new supply into the market and by implication consumers will pay either via by taxes or network costs the difference between the price required to justify new entry and the price received in the market.

On the face of it that’s about $10-$15 /MWh. Secondly, the numbers also reflect that price insensitive behind the meter solar continues to be installed, forcing middle of the day prices towards zero for much the NEM in much of the year. And yet the numbers still feel too low no matter how much modelling we do.

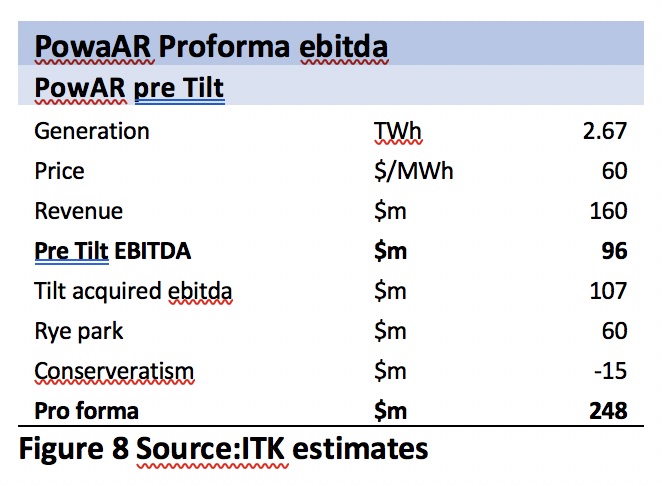

Let’s turn briefly to the 20% equity investment in PowAR. Our comment would be that if AGL doesn’t manage this relationship very clearly it will be part owner of a competitor rather than a partner. Having a 20% equity investment, and management of some, but going forward, less than half the capacity, brings, in our opinion, only a limited voice to the table.

PowAR is notionally bigger than NAGL

AGL owns 20% of PowAR, and post Tilt merger purchases some of its output and provide asset management services for the pre Tilt acquisition assets.

Our understanding is that AGL has access to output from new projects at PowAR but neither an obligation or sole access.

Post completion of the Tilt acquisition, and assuming the 400 MW Rye Park wind farm is built, but not including the likely construction of the 1000 MW Liverpool Plains wind farm, we estimate PowAR will produce around 6 TWh of energy from about 1.7 GW of capacity.

If we include NAGL’s yet to be finally confirmed batteries, you could argue that between PowAR and NAGL there is a nice balance of firming power and bulk energy.

PowAR of course has significant development opportunities through the Tilt acquisition and also access to the capital to build out the portfolio.

However, we can’t see PowAR being content to simply be a price taking PPA provider. It’s a big business now and as a result it’s going to increasingly look for its own vertical integration and ability to firm up its own bulk energy.

To have a portfolio of customers and in short to look like a modern gentailer.

We guess as much as $250 m of Ebitda post Rye Park and also assuming full operation of Coopers Gap, the biggest operating wind farm in the NEM that has a wind resource identified by none other than the renowned Windlab team.

In our view this makes it comparable to or even bigger in Ebitda terms than NAGL although NAGL numbers are so uncertain as to make estimates hardly worth doing.

You could add in some PowAR equity earnings to NAGL, but after interest, tax and depreciation there won’t be much, and there are no doubt many errors or misunderstood things in the above analysis.

You could find more about this article on the website reneweconomy.com.au HERE – Author: David Leitch

You could read more about Blue Green World Here, about Publishing World News Here, about You read, we publish Here